Computational Thinking: Abstraction

This page builds on our introduction to computational thinking. Recall our five foundations of computational thinking:

Abstraction

Abstraction involves ignoring details that are unnecessary for the current issue at hand, and being able to talk about and reason about a thing apart from those details. We purposely say thing because it could be a concept in our world, a problem we are trying to solve, or a software system we are trying to develop.

Wikipedia:Abstraction says “Thinking in abstractions is considered by anthropologists, archaeologists, and sociologists to be one of the key traits in modern human behaviour”. Abstraction is everywhere in our lives, so why treat it as a foundational idea of computational thinking? Really for three reasons:

- computers are binary digital electronic devices built out of very simple devices but at scales that make them extremely complex;

- software itself is built out of very simple basic operations that need to be combined and used in very complex ways; and

- building software to solve real problems necessarily involves managing complexity by deciding what to include and what to ignore.

You can see the theme in those three things: abstraction manages complexity.

A critical part of abstraction is naming. Naming things is fundamental to humans being able to think and reason about things. Indeed, some say that language is one of the critical aspects of being human.

When we come up with a new abstraction, we usually have to give it a name so that we can talk about it as a single thing. If you think about many of the “modern” words that you know – words that were invented recently – many of these words are names of new abstractions that have been devised. Social media is a name of an abstract class of computer applications that allow people to interact in some way. Post is the word (name) we use to talk about many kinds of messages we put out on social media.

Abstraction Form 1: Ignoring the Irrelevant

One form of abstraction is understanding what details are relevant for the issue at hand, and what details are irrelevant.

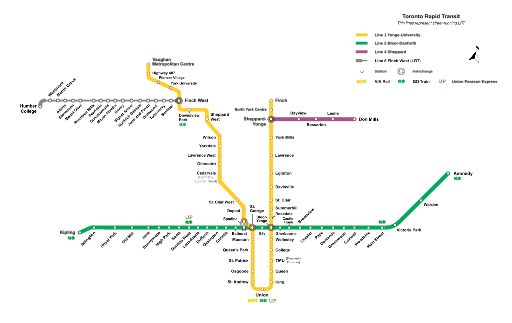

A good example of an abstraction that focuses on relevant information is the modern city subway map, as shown in the Toronto map below (CC from Wikimedia):

This map shows approximately north/south/east/west directions but it does not try to be geographically exact; it mostly spaces out the train stops equally, with some longer spacing to show more distance, but again not exact distances. It uses bright colors to distinguish the train lines, and shows connecting points where passengers can transfer trains. It makes it very easy for a user to find how to get from one stop to another, without all the complexity of looking at a full city map. That’s the power of abstraction! BTW, here’s a history of subway maps.

Most things in the real world have too many details for us to ask the question “What should we ignore?” Rather, we should ask “What do we need to know for the issue we are dealing with?” By answering this, the things we should ignore are implicitly decided (by ignoring them!).

For example, if I am going to create an online bookstore, I don’t need to know how tall my customers are, but I might want to know (eventually) what kinds of things they like to read. However, if I am going to create an online clothes store, it would be the exact opposite: I would want to know (eventually) what clothes sizes they wear, but I don’t care about their reading habits.

We sometimes call the collection of details we need to know a conceptual model of the actual thing. An actual customer is a person, with a huge number of possible details abou them, but the conceptual model of a customer for a particular online store is only those details that matter for that store.

When we are creating an abstract conceptual model, we call those details the attributes of the thing (or entity) we are modeling.

Abstraction Form 2: Finding the Generalization (and Specialization)

The second form of abstraction that we do in computational thinking is understanding how something we are thinking about generalizes, and then what are the specific, or specialized case of it.

For example, suppose that we are creating some online banking software. We first need to think about banking in general. We start listing what customers do, and we first write down deposit and withdrawal. But then we step back and think: oh, there’s a higher level concept here: the idea of a transaction: an operation that changes the balance of an account by some amount, and the balance of another account by the negative of that amount (possibly adjusted by fees). Transaction is an abstraction. Every account transaction is of some particular type (deposit, withdrawal, transfer, etc.), but they are all transactions.

Identifying the abstract idea of transaction helps us better organize our understanding of banking in general, and what our software will need to support, and ultimately helps us in designing and building our software. In object-oriented programming (OOP), transaction would be identified as an abstract base class. A base class is a category of very general kinds of objects, and calling it abstract means that any object of this class is of some specific kind of sub-category, or subclass.

Another easy place to see abstractions is in biology, in the categorization of living things. For my dog Barney, the categorization is:

Barney is a border collie, which is a dog, which is a mammal, which is an animal.

Each level to the right is a higher level of abstraction; Barney is an actual thing, or object.

Mammal, for example, is an abstract base class. We never point and say “Hey look, there goes a mammal!” Every mammal is of some specific subclass, so we might say “Hey look, there goes a dog!”. We might say “there goes an animal” if we don’t see it very well, but that is using the word animal differently than the biology-specific classification usage.

Exercise Questions

To work on using these two forms of abstraction, consider the following exercise questions. You can do these over and over with many different ideas.

-

Name either a) something in the real world or b) something that we do in the real world. “Real world” does not necessarily mean physical, it could be within, say, a game we want to play or in other mental aspects. We will call this thing or activity our concept.

-

Think of a software (or hardware) application that might have to relate to that concept. We will call this our app. (note to self: I want to say “domain”.)

-

Name a relevant attribute of the thing for the app. Repeat a few times.

-

Name an irrelevant attribute of the thing for the app. Repeat a few times.

-

Find an abstraction above the concept. In other words, is there a more general concept? Multiple layers of generalizations?

-

Find a specialization of the concept. In other words, are there specific sub-concepts?

You can repeat from 2-6, using the same concept from 1 but a different application for 2.